During my initial interview with Stephen A. Scheer posted in June, I learned of his experimentation with multiple exposures. Many of these photos were published in the 1991 book Wave Hill Pictured, which is long out of print but still available on the secondary market. It's well worth seeking out. After seeing the book I probed Scheer about some of the images. Unless otherwise noted, all images shown here are from Wave Hill Pictured.B: How did you get the idea to do multiple exposures? SS: My work with multiple exposure photography began as an experiment, where I wanted to do something unusual with lighting that I had not done before. I used a lot of strobe in those days as a commercial photographer and my interest in controlled light carried over deeply into my art work. What I liked about technique in photography was problem solving. That is how the multiple exposure work began.

Were you shooting other stuff with that method at the time? For example, did you shoot city scenes with double exposures?

Were you shooting other stuff with that method at the time? For example, did you shoot city scenes with double exposures?I did some street work in New York with multiple exposures, but only for a short while. An interesting method I used was a form of re-photography, where I photographed projected slides of people onto previously exposed films of architectural subjects.

LOTTO-NYC, 1989 is an example of that. The mailman in the blue suit with a cigarette in hand was shot as a 35mm Kodachrome slide. The smoke shop facade was shot in 4x5. I projected the 35mm slide onto a white surface and re-photographed a masked portion of it right onto the previously exposed 4x5 film.

LOTTO-NYC, 1989, Stephen A. ScheerHow planned were the pairings of your exposures? How much control did you have?

LOTTO-NYC, 1989, Stephen A. ScheerHow planned were the pairings of your exposures? How much control did you have?I devised several ways to make the pictures, but they all worked by mixing strobe light with available light in carefully controlled ways. For the square pictures, I used two cameras with a film back that could go from one to the other.

Hands, Guitar, Hat, Wheels, Chair, NYC, 1988, Stephen A. Scheer

Hands, Guitar, Hat, Wheels, Chair, NYC, 1988, Stephen A. ScheerFor the rectangular pictures, I only had one camera, which was more challenging by way of its limitation, but with experience I managed it. All the pictures were in-camera. They were not manipulated in processing. I used b&w Polaroid film to create them and color negative film to keep them.. I did some still life and figure work in the studio too, as in

Hands, Guitar, Hat, Wheels, Chair, NYC, 1988, but most of the work was landscape with still life elements that required a responsive awareness of the changing natural light as I improvised with strobe.

How often did you look at the Polaroid and realize the negative wasn't worth pursuing? Or were you usually successful from the start?

How often did you look at the Polaroid and realize the negative wasn't worth pursuing? Or were you usually successful from the start?I used Polaroids to physically make the pictures in a step-by-step fashion, to see what I was doing in the making. If something wasn't working, I changed my approach. I made Polaroids of each component separately, and then a Polaroid of all the components together before I committed to using the color film to do the same.

When thinking of combining two images what were you looking for? Formal elements, or colors, or subject matter? What made you match X photo with Y photo?

When thinking of combining two images what were you looking for? Formal elements, or colors, or subject matter? What made you match X photo with Y photo?An in-camera multiple exposure picture is an accumulation of the light used, in a synthetic way, to make a new picture that is different. A piece of film is continuously sensitive. If you light up individual things you can string them and blend them together. So, instead of matching X photo with Y, I was actually thinking about making Z photo from XY parts, where Z is the end product and entirely different. In the Wave Hill pictures I was most interested in putting together architectural elements with lush landscape scenes to make new pictures with changed contexts for each element, to reorient the expectations of the viewer.

Do you think multiple exposures have any art or future now with the dominance of Photoshop? It's so easy to combine images now, is there something in the original film method that's missing with Photoshop?

I can’t compare my methods to Photoshop, except to say that my work was in-camera, in the live moment of photographing, and Photoshop is a post-production tool that allows for after thought. My landscape work was spontaneous, improvisational and time restricted, whereas Photoshop is timeless and repeatable. Both methods are deliberate, but with film you can only add as you go, you cannot take away. Photoshop allows for reduction, where you can eliminate things that you don't want. I usually manage to avoid things I don't want, rather than accept them with the insurance that I might discard them later.

I think what I'm asking is how or if the process is fundamentally different. With in-camera multiple exposures you don't know what you've got until you make the image (although Polaroids can let you see it quickly). Whereas with Photoshop it seems more fluid and experimental. You can combine and match images in a second, then reverse steps and try something else. I'm curious if you think either process leads to a particular type of image that you might not get from the other process.

I think what I'm asking is how or if the process is fundamentally different. With in-camera multiple exposures you don't know what you've got until you make the image (although Polaroids can let you see it quickly). Whereas with Photoshop it seems more fluid and experimental. You can combine and match images in a second, then reverse steps and try something else. I'm curious if you think either process leads to a particular type of image that you might not get from the other process.I think you may have answered your own question about Photoshop, about its fluidity...and I have not used it to make multiple image pictures yet. But, it seems to me to be more like collage and less like transparency, because it is done with combined layers instead of continuous light. But, Photoshop is clearly the ultimate way to edit the contents of a picture, for example, to put together a seamless combination of disparate images that reads as continuous. Photoshop does this better than it does simulations of multiple exposures.

How do you see these multiple exposures fitting into your career as a whole? Were they just an experiment long ago, or do they relate more closely with your other photography? To me they seem quite different but maybe you see them as more related?Generally I would agree, that they seem quite different. But, the same person made all the work. I think a photographer experiences "flow", as a sustained intuitive production, when their subject is clearly realized and defined. When the subject is understood, the work just comes. I know I experienced this with the Maples work, the Texas work, and I am experiencing it now with my New York architectural work. There were other times when I made interesting work, maybe even great work, but I might have been reacting to another person's work.

With the multiple exposures, particularly Wave Hill, I knew I was doing something that hadn't been done before, or at least hadn't been done very well, and that was - multiple imagery done in-camera, with natural and artificial light, in color and on location. The nominal subjects were not as important as the creativity of the process, and I experienced that as "flow" too, where what I was doing, and how I was doing it, was more important than what it was actually of. So, the multiple exposure work is different in how it defines itself, as process driven more than subject driven, but the spirit of the work is similar to other things I have done.

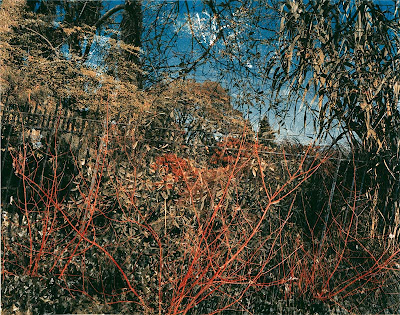

Can you briefly discuss what went into making these two images? Wave Hill Pictured, Plate sixty-three

Wave Hill Pictured, Plate sixty-three

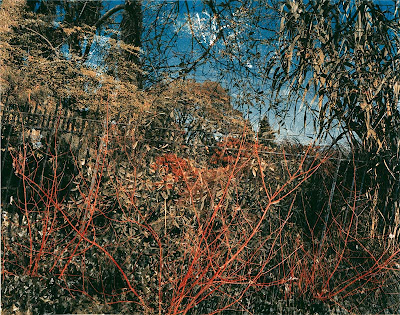

Wave Hill Pictured, Plate sixty-twoHow did you choose the pairings? How conscious were you of how the forms would line up? Can you put the images into the context of process?

Wave Hill Pictured, Plate sixty-twoHow did you choose the pairings? How conscious were you of how the forms would line up? Can you put the images into the context of process?In these two pictures, the idea was to put the architectural element, like the bench or the columns, into the landscape, in such a way as to make a new still-life picture.

Plate Sixty-three was made with two stationary roll film cameras in two locations about 100 feet apart. First, the bench with foreground leaves and gravel were made with one camera. The front part of the bench was illuminated with strobe light and the rear part of the bench with sunlight. The background was left underexposed.

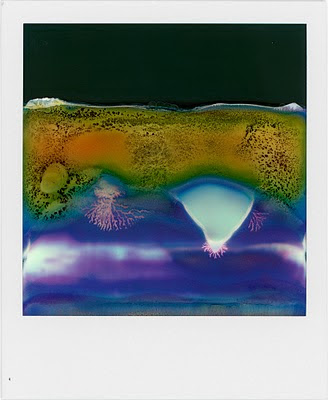

Polaroids made in preparation for Plate sixty-three

Polaroids made in preparation for Plate sixty-threeNext, the magnolia blossoms and branches plus background and sky were made with the second camera, using strobe light on the branches plus a fair amount of daylight everywhere to raise the shadow and mid-range values throughout the scene. The different variations of image clarity, see-through transparency, and layers of illumination were controlled by the mechanics of the camera and strobe light, while the natural light moved and changed. The film was transported from one camera to the other with the second exposure following the first exposure right away. It probably took about four hours to complete, which meant that I had to plan ahead in anticipation of the movement of the sunlight.

Plate sixty-two was made with one view camera in two locations several days apart. The cement columns, lit with strobe, and the background lit with available light, were both part of the first exposure.

Polaroids made in preparation for Plate sixty-two

Polaroids made in preparation for Plate sixty-twoThe second exposure, done days later at a different location, was of the flowering blossoms and stems, as seen through hanging boughs, in the middle of the picture. They were lit with strobe. The major difference here was that I could not go back to the first location to redo the first exposure if I did not like the way the second exposure was working out. But, the final image was on a single piece of film, as was the case with all my multiple exposure pictures. That defines an in-camera multiple exposure as compared to sandwiched negatives, multiple printing or Photoshop. It is done in the camera on one piece of film.

After my cousin died recently I noticed that many of his parents' Facebook friends began changing their profile picture to Colby's. It seemed like an easy way to pay my respects so I did it too. There was no mass alert. Everyone did it on their own.

After my cousin died recently I noticed that many of his parents' Facebook friends began changing their profile picture to Colby's. It seemed like an easy way to pay my respects so I did it too. There was no mass alert. Everyone did it on their own.