It was a few years ago that I first encountered Stephen A. Scheer's photographs in Sally Eauclaire's books, first in New Color/New Work and later American Independents. I was struck immediately by Scheer's wonderful feel for composition and color, and his ability to find photos in unusual places. His style was simultaneously streety and formal. Who was this guy? I wondered. How come I haven't heard more about him?

Those questions set me on a gradual hunt tracking down some of his other work and finally to Scheer himself at the University of Georgia in Athens, where he teaches photography. We exchanged a series of emails and he was kind enough to answer some questions about his past and current work.

Scheer's many awards include an NEA Fellowship in 1980 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2001. His photographs are in various collections including MoMA, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Museum of the City of New York, and his work has been featured and reviewed in Aperture, DoubleTake, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, and The New Yorker among many periodicals. His most recent project Interborough New York is a longterm photographic narrative documenting New York City.

Manhattan and Bergen County, November 16, 2001, Stephen A. Scheer

BA: Can you briefly trace your photographic path?

SS: I started doing photography, which I would define as making my own negatives and prints as well as shooting, when I was in 8th grade, about age 14. My science teacher was really a photographer and he organized a group of students who wanted to learn photography. I got involved with the group and before long I was leading it.

I was initially interested in humanist photography, as differentiated from photo-journalism. My mother took me to see the exhibition "Harlem on my Mind" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1968, and I also had a copy of Steichen’s "Family of Man" from the 1955 show at MoMa. I was generally interested in looking at LIFE magazine and I knew of photographers like Cartier-Bresson, Eisenstaedt, Dorothea Lange and Gene Smith, but the first photographer who I studied intensely was Edward Weston and I think it was because I was making negatives and prints and his were the most amazing I had seen. Then came Harry Callahan, harder to understand, and Paul Strand, harder to find. My science teacher was a devotee of Minor White who I tried to understand but could not, except for the technical concentration which was actually superior in the work of Ansel Adams, and so I read Adams' books many times over because I was self taught and needed to.

Street photography came to me or me to it, later. At 17, I took a workshop with Garry Winogrand. I was teaching myself the view camera and he was talking about Robert Frank, and you can see how I adopted an eclectic approach to photography starting then.

Do you have specific memories of that workshop?

Yes. Winogrand was highly opinionated and passionate about photography. He looked at pictures quickly and impatiently, because he was experienced and very much in touch with what he was looking for. He described pictures that he liked as being “loaded”. He gave the group an assignment to photograph in front of a particular post office on a particular day at a particular time, 12:00 noon. We were amused to be there all together with cameras, but Winogrand was dead serious about it. Another day I saw him photographing in the street in the late afternoon with a flash on his camera. Turning left then right, then around, back and forth, frantically shooting everything. He liked to joke about giving people a sunburn at close range with his flash. This was 1971.

I wasn't nearly as impressionable as I was hungry, and it wasn't just with photography, but I was shy and that was difficult and photography was something tangible that opened my mind to the world.

When did you start doing color photography?

Color photography did not come to me. I came to it. No one I knew was doing it or knew how to do it, beyond shooting Kodachrome or E4 or C22 and sending it out - always sending it out.

It was 1975. I saw some demos and then bought supplies and taught myself, making color negatives and prints in my bathroom - 35mm, 6x6cm and 4x5, for a few years until I went to graduate school starting in 1978. Things were happening quickly. I already knew about Eggleston, Shore and Meyerowitz, and I was discovering Helen Levitt and Joel Sternfeld. I was working in different ways, but in my color street work, which began after graduate school, I was devoted to the uniqueness of Kodachrome, even though there was no good or practical way to print it at the time.

So you were working during that time with no way to see the results, or to show them to others?

I had an excellent projector and every night I would look at the work from the day before. I taught myself how to make large inter-negatives from my slides, which I then contact printed. Years later I had some dye transfer prints made and eventually I went back to color negatives when T-grain films came out. We’re talking about street photography here, and that is what I did in 35mm. I also did non-street work in medium format that printed nicely in color. Printing 35mm color in the early 1980s was troublesome, but viewing and knowing and learning from the slide work was fast and exciting.

The 35mm camera made street photography what it was, and if it had to be color it had to be Kodachrome. So it wasn't about prints, it was about the work - people, drama, gesture and narrative meaning. Helen Levitt was the best color street photographer.

What is it about Levitt that you think sets her apart?

She was a great color street photographer because she was a great photographer period - and the color came later, which makes a lot of difference because she came to it with experience and maturity. By deeply understanding the human nature of her subjects, and I’m stressing her sensitivity to the hardships of women and children in the poorer sections of Manhattan over many decades - Levitt did not rely on form to show us what she saw and felt. It was the subject that was important and that made the color immediate, and believable, and in her case urban rather than natural. Other color photographers of the time were burdened with the need to prove something, like the sensuous value and descriptive power of color.

What was your work process back then? Were you shooting for an outside project or just for personal use? Did you always have a camera with you or did you set aside dedicated blocks of time to shoot?

If I wasn't carrying anything else or going somewhere by appointment, then I would carry a camera because I was out - out for hours, day or night, that is dedicating blocks of time to shooting. I'm not sure what an "outside project" is. I did commercial work if that is what you mean, but strictly by assignment. It was always planned with other people and lots of equipment and long hours from start to finish.

With my own "personal work" there wasn’t a sense of finish. My method was to look at the world explicitly with the intent to make pictures of it, because that was the best way for me to relate to it. I wasn't a voyeur, I was a picture maker. I was interested in people in pictures, at large. I didn't have time to know everybody. I'm not sure why others call this "personal work". It is actually rather physical, energetic and public. You maneuver and interact with people. They are subjects for pictures and your job is to make sense of them and it, photographically.

By personal I meant driven by internal motivation and not by commission or some other outside force.

There are also people who do commissioned work in response to an internal motivation that compels them.

Let me ask that another way. What led you to specific locations for the Texas work in American Independents? Did you drive around and look for scenes, or wait outside public buildings, or what attracted you to shoot in certain places?

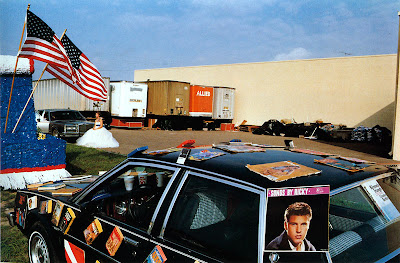

I was invited to go to Texas to teach photography at Rice University in Houston. I was paid well enough to travel around. Every weekend I went somewhere different, usually far, by plane and then car. I researched where certain events were taking place like homecomings, and I went. The Texas work was very public, but not necessarily tied to the street. There were many rural locations where the landscape played the field to human events.

Did you find certain subjects to be intrinsically more interesting photographically, or is the visual universe a pure democracy of equal photographic opportunity?

I'm sure the "visual universe" is not a pure democracy of equal photographic opportunity. There are many places with laws restricting free and open photography. Any place where human rights and free speech are denied is also a place where photography is denied. But to the intended meaning of your question, still the answer is no. I do not think certain subjects are more interesting photographically. It is rather that certain subjects lend themselves better to the idiosyncratic treatment of the medium than others.

For example, photography that prefers a conceptual explanation of its subject is often less visually oriented than photography that presents a subject for what it is, and when photography becomes less visually oriented it fails as a picture making medium.

So conceptual photography is an invalid approach?

Any photography that is rigorous about its content and the meaning of its subject in relationship to its form, is both visual and conceptual. But if the idea of the photographic work is genuinely more compelling than its form, then you have a problem where the choice of the medium should be called into question, as perhaps something other than photography should be used.

What do you mean "the choice of medium should be called into question"?

That perhaps another medium like writing for example, would better express the experience when the concept attempted has been visually compromised by a kind of photography that doesn't show very well, what it is trying to tell.

It's hard to think of any photo that would be more clearly expressed in writing.

I am talking about the concept, not the photograph, that might be better expressed in another medium. There are just certain concepts that photography does not handle well, like "darkness" for example, because it is trite to illustrate that. I cannot think of a good picture of darkness that does not also include a contradictory dose of its own nature, that of light. It is elemental to any practice of photography that some things work and some things don't - and for the things that don't work in photography, try another way to do them.

Do you see concept-based photography like, e.g., Crewdson or Wall, as a separate discipline from so-called straight documentary photography like, e.g., Cartier-Bresson or Evans?

I do not see it as a separate discipline, but I do see it as a different manifestation of the same discipline. I actually consider Evans to be an interesting example of one who is conceptual/documentary.

Really? To me, Evans seems like a prime example of a documentarian. There were concepts behind his projects but I don't think he ever prefabricated photographs.

You don't have to stage or fabricate a subject for the camera in order for it to be conceptual. It can also be a matter of subject and methodology. For example, the Bechers used the format of the photographic typology to make studies of industrial architecture that revealed concepts about the cultures that made them. Walker Evans did a similar thing when he photographed clapboard churches in the South. He used a repetitious approach to collecting examples of this subject to authenticate his experience of the vernacular. Same thing with his Subway portrait series, where a hidden camera was used to record the anonymous face of a culture. Evans clearly stated his distrust of the word "documentary", and he differentiated his work by calling it "documentary style", to point out that photography, characteristically, can only be known to look documentary, which is entirely a conceptual notion.

Your early 1980s color work was in square format. Do you think you saw things differently in square format compared to the rectangular form of your later work?

I would like to think not, but that wouldn’t be correct. It is also important to recognize and acknowledge their similarities, what they share of my lyrical view of the subjects. But their forms are very different because the square is axial-symmetrical and the 35mm frame is pan-optical, and it’s highly subjective as to whether you agree or not with that analysis of the potential of the picture plane. However, I will leave you with the concept that the square is the only rectangle that can contain a circle evenly on all sides, and that images projected from lenses are always in the shape of a circle. It could be argued that the square is therefore more intrinsic to optical photography, but not necessarily to the way we see.

So why shift from square to rectangular?

Manhattan, June 17, 2002

Some photographers choose to work with one format for an entire career, or make a change based on their changing view of things. I have been experimental in my work because I am self taught and wanted to know how to do the different things that have occurred to me along the way.

Are there things you're looking for now visually that you weren't looking for back in the 1980s?

I'm photographing buildings now - urban architectural subjects including infrastructure, civic buildings, parks, waterways. I'm working in New York. There are people in the pictures too, but the concentration is architectural. Working in and around streets, it is public. It is black & white.

The main difference now is that I am now telling a story photographically. The subject has an extended narrative content. I'm making a book with many chapters that moves the subject through space and time, a continuum of 12 years. The work is about the outer boroughs of New York. It is perhaps a form of street photography because it is in the public domain and it is urban. The emphasis is architecture though, and it isn't 35mm. It is more of a visual prose than poetry. Can it still be defined under the umbrella of street photography, say like, Atget's pictures of Paris? I'd like to know what others think.

The main consistency I see connecting your 80s color work and the recent New York photos is your concern with form. You seem to take pleasure in fitting buildings and urban elements together the same way you once fit people into a scene. Proper viewpoint is crucial.

How do you know when you've found the precise spot to shoot from? Do you know instantly, or is it more of a detailed search, try one spot, then another…

Finding the precise spot to shoot from is a complicated matter of choice driven by several factors including: physical access and appropriate distance, qualities of light, and the order of need in considering the pictures I have already made and still want to make in a given place. I tend to be highly selective and decisive. For each picture there is only one composition, but I often photograph the same building from different positions over time.

Are you conscious of searching for that formal element, or is it so ingrained that it is subconscious?

It is not subconscious, it is attuned and requires great concentration. It can however become ingrained or habitual. I mentioned earlier that Helen Levitt did not rely on it. She learned well from the example of Cartier-Bresson’s early work, which was direct and intense. But she also understood to avoid the trappings of journalistic style as form, which predominated much of Cartier-Bresson’s later work under the guise of "the decisive moment".

What interests me about putting buildings together in pictures is the photographic observation and commentary on the history of the development of a place. From the first half of the 20th century in New York you can see the proximity of building types that made neighborhoods. For example – an armory will often predate a nearby hospital, that coincided with the building of a church, that had a school and a park to go with it. Scenarios like this played themselves out in a few short decades. In the latter half of the 20th century you can also see how major highways like the Brooklyn Queens or the Cross Bronx Expressway cut through neighborhoods like the one I described above and forced the isolation of some of these buildings and caused dysfunctional relationships between the neighborhoods at large and their civic architecture. It takes a series of pictures for me to convey a context like this, not just a single picture. If you only see form in the series, then you don’t understand the subject.

Your recent shift to monochrome seems to run counter to the more common pattern of beginning in b/w and shifting to color. Why the switch?

My background in photography was originally black & white, as was appropriate for the time, starting in 1968. I began making my own color pictures in 1975, and from then on to around 1991, I worked predominantly in color, but I never abandoned black & white. In the still pre-digital era of the early 90’s, I felt that I had mastered color photography, and after an intense preoccupation with multiple exposure photography in color, I changed my mind about what I wanted to do.

from the book Wave Hill Pictured, 1991, by Jean E. Feinberg

On the other hand, I don’t think one can fully master black & white photography because the world does not exist in black & white and there is no certainty about how it should look in monochrome. The process is more abstract and more individualized than it is with color. Black & white is the original idiom of photography, more of an illusive means - and color can be an end, an achievable goal, and that is why it can be mastered, even more so today with digital control. That doesn’t mean that color is less interesting. It’s just that color photography adopted its idiom from sources other than photography itself, like from painting for example. And today, color photography continues to reinvent itself habitually without alternatives, because the photographic industry dictates color.

Are you religious? What is your understanding of unexplained coincidences?

I doubt that religion has anything to do with it, but I can tell you that coincidences in photography are explainable. Coincidences are made all the more visible by the optical recording system and therefore are able to be studied to the point of conclusion or in-conclusion, and if it is the latter, then that is due to a lack of information in the recording system which is the cause for the uncertainty. It is our deficiency if we cannot explain something that we can see. Religion is something else. Unfortunately people use it, or I should say misuse it, to rationalize their deficiencies or excuse what they don't understand.

Maybe religious is the wrong phrase. I think what I'm trying to ask is, do you believe in any level of order beyond that which is immediately apparent, or are you more agnostic? When you make a great photo like, e.g., Maternity Ward Steps, Houston, Texas from American Independents, in which every element is in the right spot, does it spark any wonder about how that came about? You're standing there and all of the sudden the baby is lifted into the air. Does it make you curious why that happened, and why you were prepared for it?

Practice makes perfect and hard work combined with the experience of knowing, plus good timing, allows a well-tuned sense to act and seize a subject. This is different than "the decisive moment", which deals more with formal relationships than specificity of subject. And then there is the possibility of Karma, which may be the answer you are looking for, but there are actually many more failed attempts than there are successes, and so there is patience and luck too. I look for situations where pictures may have potential and then I get to work. It is not unusual to find people carrying babies to and from maternity wards. But yes, I have to know what I’m doing and how to position myself and be ready to rise to the occasion when someone lifts a baby into the air.

Which photographers are most important to you?

Since I have been a student of photography for about 42 years, the list of names would be rather long. I should add Walker Evans to the names I have already mentioned in answering these questions, because he is the model for so many of them too, except Atget, Strand, Weston, Lange and Eisenstaedt who have earlier origins, or Callahan who is of different photographic lineage than Evans. I also admire great anonymous photography because I am ultimately more interested in photography itself, than in photographers.

So you think the central unit in photography is the medium itself and not the artist. Photographic history has generally been constructed around personalities. Is this backward?

The biographical history of photography is constructed around personalities, but the productive history of the medium, ie: what has been produced, is more complicated and tends to be caught up in the development of photography’s technology and the cultural expression and economic means of people around the world who have used it – artists, professionals and amateurs.

Maybe the better question to ask is, which photographs are most important to you?

I don’t think I can separate individual photographs from their makers, but over the years I have looked at a few things many times and always saw something new.

For example, Lewis Hine’s Empire State Bldg. series, Paul Strand’s early New York portraits - like Blind Woman, Charles Sheeler’s Ford Motor Plant, Edward Weston’s Point Lobos series, Harry Callahan’s multiple exposures of Eleanor, Weegee’s tenement fires, Lee Friedlander’s nudes and Diane Arbus’ Jewish Giant at Home with his Parents.

I would have to say that the greatest pioneer of American photography, and American may only be important to me because I am one, is a photographer who was born essentially at the dawn of photography, Carleton Watkins. I say this because he had the opportunity to invent for himself a way to look at the world with photography, more than he had need or reason to make pictures at all, which could have been addressed by other mediums or done by other practitioners of the time.

I love your analysis of Watkins. I think this point goes to the heart of why people take pictures. Photography is so established now, particularly "Art Photography", that people who set off down that path often do so now with some goal in mind of how photographs should look. Rather than just be led by the camera, they want them to look like what they've seen in galleries or books or the web. I'm generalizing but I think you get the point. So maybe it's harder now than in Watkins' time to make wholly original work.

What about contemporary photographers? Are there any you particularly admire? I'm trying to get a sense of what you think of the contemporary photo world and if/how candid street photography fits into it.

One interesting photographer who works with urban subjects is Camilo Jose Vergara. His book The New American Ghetto is fiercely authentic in its challenge to deal with a complex subject over time. It is clear though that the "artistry" of his camera work, being less important to him and the way he sees his subject, keeps his work at arms length from the art world. But, I do not consider him a photo-journalist.

Generally the contemporary photography world is immersed in its commercial and technological revolution. It’s hard to see that it’s about consumption because so much of it is in cyberspace, but everyone has a digital or cell phone camera and everyone is a photographer.

"It's about consumption." Can you elaborate?

John Szarkowski once commented that ’there were more photographs in the world than bricks’, and that was probably 30 years ago, plus or minus. I think it might be possible to say now that there are more photographs in the world than anything else. I think that says something about consumption.

Most street photography takes place in cities. But as your 80s color work shows, it can very well take place in less urban areas. To what extent do you think street photography is tied to cities as specific subject matter, and to what extent is it a mental approach? Can street photography happen anywhere? If so, what is the common thread?

Urban can encompass the suburban or the city and in between. Street photography is also stylistic and therefore has some commonality with "documentary" and "reportage" in that it is a hybrid of the fictional and the non-fictional in terms of observation, perception and experience. The term “Street Photography” embraces more than it states, forcing it into metaphor when attempting to define it.

If street photography were defined more broadly as urban photography in the public realm, then there would be a lot more of it out there. The question arises today as to whether it is manipulated or not, and disclaimers are now needed to identify "straight" work. There is also the issue of "privacy" in the public realm, which is problematic because a camera in the hand should not be any different than a sketch or note book in the hand, and the smart phone today enables anyone to combine images with messages for immediate broadcast. An experienced street photographer is a discreet and intelligent artist - observant, patient, decisive and bold, and may be aggressive in the proactive sense that empowers action. If you consider all the components that make street photography an act, then yes, you can say that street photography embraces a mental or a psychological approach, in order to give meaning to the physical.

What sort of acceptance did your 1980s photos have in the contemporary photo market at the time? Did you put much effort into promoting your work?

I was of the generation of the "New Color Photographers". My earliest publication was in Aperture #91 in 1983 of a body of work called The Maples, which was well received.

There were several exhibitions and publications that followed, but in terms of the photo market, your question, there was very little monetary return. For me it really was an art world, art museum, art book/magazine visibility, that also involved education and I taught photography far and wide.

The art gallery world is entirely different. It is commercial and measured by dollars. If it doesn't sell it won't be in galleries very long. I certainly promoted my work. I was new. That's what the contemporary art world wanted and still does, novelty.

Indeed. I think your answer highlights the potential tension between galleries and museums. Galleries are generally the first stop, meaning you can't really get into a museum collection until you've had a few shows. So often the work that finds its way into museums is filtered by the market and not just aesthetic concerns. Do you have either of these particular audiences in mind for your recent New York work?

I would refer to them as venues, not audiences; I think an audience refers to people ….but, yes I do have them in mind. The Interborough New York website is designed to work like a book, so my plan is to publish the work in some similar form when a good publisher is willing to take it on. At the same time I would like to exhibit the work. In a gallery I could show a small selection and in a museum I could do more. And it doesn't have to be just prints. I am also interested in video projection because there is a lot of work involved and it is arranged in a linear way that projection could accommodate nicely. If I make a book out of Interborough, then I will also make some books on the older work we have discussed here, because I have some good ideas about how to make them now.

8 comments:

wonderful interview. Very thoughtful take from a different perspective. Thanks for posting it.

This is what I come here for. Thanks.

I second john, a great interview. And it is not that often to read people who articulate their thoughts so well. Now I have to re-read it a couple of times. Thanks to both of you.

So, B, do you believe that otherwise unexplained coincidences, such as appear in some photographs, might have a religious explanation?

If I could explain unexplained coincidences they wouldn't be unexplained.

But coincidences exist. Sometimes there are photos in the air and the feeling is palpable. Sometimes there aren't. The flow does not seem completely random. Which makes me wonder sometimes when I'm shooting how it all ties together and what it all means.

Most religions don't have good answers to these questions. But the resulting photos often provide clues...

Kind of like the I Ching, maybe.

Much appreciated, Blake and Stephen.

This is piece excellent in many ways, congratulations to Stephen and Blake – and thank you. Thoroughly enjoyable and educational to read. Though I have known Mr. Scheer since just after he moved away from his science teacher There were many things I learned in this well written and far ranging dialog on photography.

Hopefully it will lead to a thick monograph on Stephen Scheer’s work – maybe on the 50th anniversary of the plying his craft, which as he said about Winogrand, Stephen has been dead serious about for a very long time. The decades of work reveal a full and careful range of work with a thoughtful center.

The new work is less sexy, but is powerful and may well find a more timeless place in the “everyone is a photographer” world we live in. I hope so.

Onward! Jim Boorstein

Post a Comment